The shophouse, or rumah kedai, is a distinct architectural typology found throughout Southeast Asia, from bustling Kuala Lumpur, to jam-packed Jakarta, and even in the relaxed holiday town of Phuket. A site of commerce and community, this seemingly commonplace building holds within its walls cosmopolitan influences that created a unique local solution that satisfies economic, social and aesthetic functions.

Chinese roots

When Southern Chinese traders arrived on these shores, they brought with them building techniques and architectural structures that would evolve, from as early as the 15th century through to the 20th century, into a local vernacular style known as ‘Straits Eclectic’.

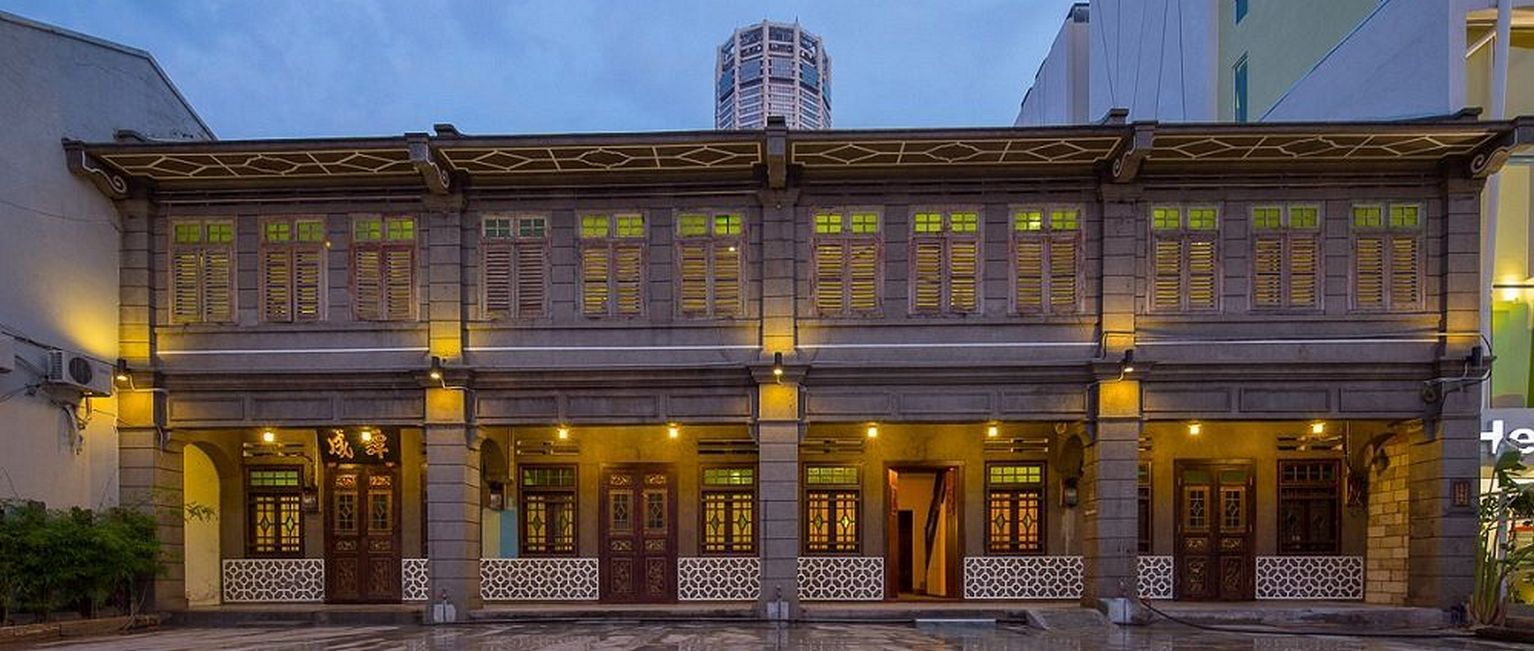

Among the most ubiquitous is the shophouse, where small-scale enterprises could operate, while also housing the multi-generational family proprietors. The ground floor is used for commercial purposes, while the back section and upper floors are residential spaces. These aptly named shophouses would be neatly lined up against each other, with brightly decorated street-facing entrances, clearly signifying the variety of goods and services offered, often in multiple languages.

Colonial Straits Settlement cities - Penang, Melaka and Singapore - are famous for rows upon rows of these shophouses, while Kuala Lumpur’s most striking examples can be seen in the bustling Petaling Street area, one of KL’s oldest built-up sections, long seen as the city’s Chinatown.

“The British did not regulate the design style, so Chinese builders constructed spaces and façades mainly based on the Chinese way,” says architect, urbanist and historian Dr Yat Ming Loo, who has studied how closely the shophouse is associated with the Chinese community.

Some of these typically Chinese characteristics include sloping roofs, open air-wells for light, air and water, and close proximity to each other. These shophouses are normally 13 to 25 inches in width in front, while the depth of the interior is two to four times that dimension. To allow proper ventilation in the cramped confines, full height walls are rarely constructed inside; it is quite typical for the full span of the ground floor to be bare. Usually, three to four floors in height, these shophouses also contain a single narrow ladder-like staircase.

Colonial influences

The height of shophouse construction in Malaysia and Singapore coincided with the British colonial period due to the influx of Chinese migrants at the time. British styles and regulations would have a significant impact on the Chinese model that had been transposed to Southeast Asian shores.

In the 1800s, colonial by-laws started regulating shophouse building specifications more closely, for hygiene and safety reasons, especially after the Great Fire of 1882. Flammable attap roofs were replaced by clay tiles, entire shophouses were remade of bricks and masonry rather than as simple wooden huts, and the rows of shops were separated by wider streets.

In fact, even the characteristic kaki lima, or ‘five-foot way’ pedestrian promenade in front of Southeast Asian shophouses came from the British. Under Frank Swettenham’s colonial administration, a shophouse was required to provide a covered walkway, which was at least five feet in width. This enabled pedestrians to walk comfortably sheltered from the sun and rain, and away from vehicular traffic. Of course, the kaki lima is often encroached upon by displays of wares, or even street vendors, leading to a lively place for commerce and communal interaction.

European architectural styles would also be incorporated in shophouse designs, especially within the façade. These include Tuscan and Corinthian columns, transom and French windows, cornice and dentils, as well as plaster relief panels, balcony balustrades and fanlights, a form of lunette window, often semi-circular or semi-elliptical in shape.

Localised adaptations

As Chinese buildings met equatorial conditions, various practical and stylistic adaptations arose. Local materials, like attap and native timber, were used, and fine wood carvings adorned façades, vents and roofs. Fascia boards hanging from the roof, which is an indigenous feature found on Southeast Asian houses, also became common. The boards, in the distinctive Malay pucuk rebung pattern, make roof ends more attractive and help with rain run-off, while the perforated designs allowed for better air flow.

Windows and opening were also changed to work better in the tropics: “Due to the increased depth and scale of shophouses, a more effective means of ventilation was necessary. Malay-styled fenestrations more suited to the local climate replaced the Chinese-styled openings,” writes researcher Tze Ling Li in her study of Singapore shophouses, which mirror the same process as Malaysian ones.

Tze also notes other distinct Malay features, such as jackroofs, lattice fretwork grilles, louvered shutters, single- and double-leaf timber doors and pintu pagar, a fence-door that offers some privacy while still providing ventilation.

Often, all three influences come together in unassuming yet truly beautiful style; you might find Georgian fanlights, decorated by Malay-style grilles just above jian nian ornamentation made of colourful, broken ceramic pieces.

The future of shophouses

Heritage shophouses today have found new life, rejuvenated into hipster cafes and restaurants, vintage hotels and arts hubs.

At the same time, the concept of living where you work is also gaining currency. SOHO developments, like Centrio in Kerinchi and Metro Pudu in the city centre, experiment with high-rise “shophouses” where apartments are split into multi-storey units. Just like the shophouses of old, living quarters are upstairs and office space below.

---

Photo credits:

Thumbnail: https://www.letsgoholiday.my/p/hotel-berdekatan-afamosa-bandar-hilir

Slider 1: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/780248704166842201/

Slider 2:https://blog.oliver-meili.name/2014/12/kuala-lumpur-a-changing-city/dsc_8585/

Slider 3: https://locenghartanahblog.wordpress.com/2016/10/09/rumah-kedai-lama-jadi-hotel-di-penang/