Legendary traffic jams are common occurrences in Southeast Asian cities, from Jakarta to Bangkok, Manila to Kuala Lumpur (KL).

KLites spends a daily average of 53 minutes stuck in traffic, in Manila, Southeast Asia’s largest city, the average is 66 minutes a day, while Bangkok clocks in at 72 minutes. This works out to nearly a month a year sitting idle in a car!

There is one city that has the problem licked, and that’s Singapore -- the island nation is a world leader boasting an affordable and fully integrated urban transport system.

Singapore only has 1 privately owned car per 8.25 people, while neighbouring Malaysia has the third highest per capita car ownership level in the world at 93 per cent of households owning a car.

People-centric cities

The data is clear; congestion cannot be solved by building more or better roads. In a phenomenon termed “induced demand”, increasing road capacity actually results in an increase in how much people drive in a city.

“No city has ever managed to build its way out of congestion,” UN University researcher Dr David Tan said during a talk in Kuala Lumpur in 2017.

This is where public transport becomes key, because the answer is to de-centre the car and focus on people.

“When we build for driving, we end up building against walking,” he said, giving the example of pedestrian bridges, which are built not primarily to make it safer for pedestrians, but instead so cars can drive without slowing down or stopping.

However, it is not quite so easy to emulate the success of a small city-state like Singapore when transplanted to the sprawling metropolises found in other parts of Southeast Asia.

Manila, Jakarta and Bangkok have populations and land sizes multiple times larger than Singapore, thus the ensuing logistical, political and cost implications become infinitely more complex.

A question of scale

Jakarta, Southeast Asia’s second largest city, has only been able to launch its first subway line this year, despite being plagued by terrible traffic congestion for decades.

The MRT, which serves a 15.7-kilometer route with the capacity to carry more than 2 million commuters a day, was officially inaugurated by President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, who joined thousands of residents who had already sampled the service over the preceding week’s free trial service.

The response has been positive, with other lines due to be rolled out in the upcoming years, to be integrated with the Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service, while complementary pedestrian infrastructure is being put into place.

“Jakarta is a great example of how to do more with less,” Urban mobility researcher James Speirs said. He is particularly impressed with the city’s use of bus systems.

“Jakarta’s BRT is a lesson for other Southeast Asian cities.”.

Bangkok and Manila both started building metro rail systems from 1999, but both cities have struggled with inadequate and aging infrastructure which has led to a growing dependence on cars and worsening traffic.

However, both cities are now on a mission to expand services.

Bangkok took more than 20 years of wrangling before its light rail systems finally opened for use in 1999. The BTS now operates over two lines, with an MRT system launched in 2004.

Limited penetration and relatively high fares mean that cars and buses remain the transport of choice, however, clogging highways and choking the city in smog. Road vehicles in Bangkok is estimated to number 9.7 million, some eight times higher than can be properly accommodated on its road network.

Several additional rapid transit lines and extensions to existing lines are currently under construction in the city, with the system expected to expand to a length of 260 km by the end of 2021 – this brings the entire network totalling 508 kilometres by 2029, consisting of a mixture of rapid transit, heavy rail and monorail systems.

In the Philippines, a report by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) showed the country stands to lose up to 6 billion pesos (US$114 million) a day by 2030 because of worsening traffic jams, centred around its capital, Manila.

Although the city’s light rail system has been in use since the mid-1980s, the line suffered from overcrowding, poor maintenance, and the resultant bad performance and the need for premature and disruptive structural repairs.

Further lines were added in the early 2000s, but penetration is still inadequate and today, Manila remains a heavily road traffic-dependent city.

However, recent developments will expand and improve the city’s creaking metro rail network. In February, ground was broken on the country's first 36km-long subway line, while construction also began on a 38-km railway from Manila to the northern outskirts.

KL well on track

Malaysia’s capital, Kuala Lumpur has fared better in consistently improving public transport in the city.

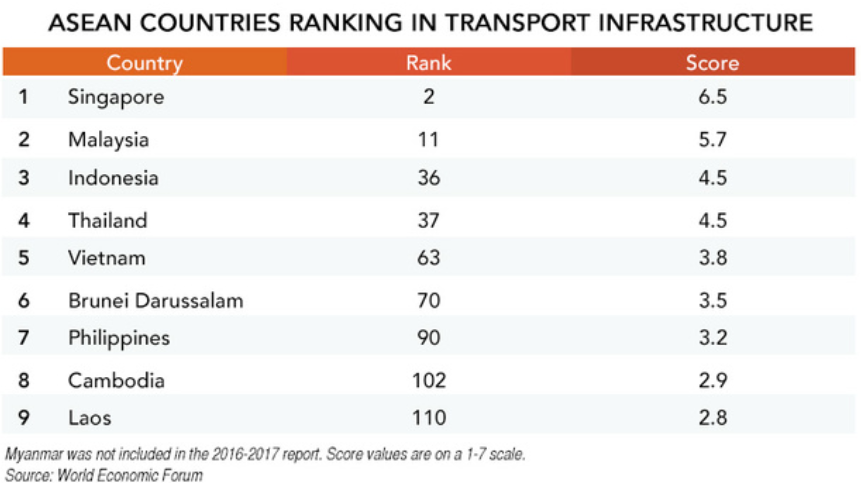

Malaysia was the only other country in Southeast Asia, besides Singapore, to claim a high spot in the transport infrastructure category of the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) 2016-2017 Global Competitiveness Report.

Singapore ranked 2nd and Malaysia took 11th spot, while all other Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries were in the bottom half of the rankings.

The Financial Times’ research arm published findings that found Malaysians get the most bang for their buck when it comes to public transport in the ASEAN region.

Kuala Lumpur joined the metro rail revolution in the late 1990s and early 2000s with the first LRT lines and the monorail. Expansion and integration continued over the last decade, and since 2012, all public transport has been integrated into a single ticketing system, covering all light rail and buses.

The whole network, which includes the six-line MRT, three LRT lines, a commuter rail system and a monorail, has now been largely integrated with each other using hubs where multiple lines meet, making journeys more seamless and comfortable.

The “last mile” of getting from door to door, the oft-cited setback for public transport acceptance in KL, is also being more seriously tackled through bus services, pedestrian crossings, upgraded pavements and covered walkways.