Malaysia’s publishing sector, mostly clustered around the Greater Kuala Lumpur area, has seen steady growth, especially since the 1990s trend of popular romances created a boom in demand. This, in turn, encouraged a raft of independent publishers to set up shop from the early 2000s.

Books are such a draw that Greater KL now has its own 24-hour book emporium located in Cyberjaya. This 37,000 square feet BookXcess outlet, stocked with thousands of books, is the largest bookstore in Malaysia.

Readers also flock to book fairs like Big Bad Wolf, which regularly attracts hundreds of thousands of book lovers. In fact, the most longstanding book extravaganza, the Kuala Lumpur International Book Fair (KLIBF) has become one of the largest literary events in Southeast Asia, reportedly welcoming around 2 million visitors in 2013.

This period marked the height of the local publishing industry which saw sales revenues of between RM1.5 billion to RM2 billion, with more than 43 publishers in operation.

In love with romance

Large corporate and institutional publishers, led by Karangkraf, found an eager, mostly female audience after it began to focus more on popular romance novels, starting in the 1990s.

The most famous is perhaps 2002’s “Ombak Rindu” by Fauziah Ashari, published under Karangkraf’s Alaf 21 imprint. The bestseller was later adapted into a hit film, starring superstars Aaron Aziz and Maya Karin, which at the time became the highest-grossing film in Malaysian history.

The boom in romance novels led to a rise in female writers and independent publishers, who as fans as well as producers, were able to respond effectively to this market segment which they understood intimately.

Academic Dr. Alicia Izharuddin, who is currently at Harvard, has been studying this phenomenon: “There is a debate (small one) that while male-dominated Malay literature has gone into a slow and long decline, popular writing dominated by women is going from strength to strength.

“Women-dominated Malay pop literature is far more democratic, more horizontal, and fluid, with readers often becoming writers and publishers too.

“For instance, I’ve met a supermarket cashier from Kuantan who became a bestselling novelist with a big fanbase, and independent publishers who are middle-aged women who start a business with their friends.”

Kaseh Aries Publication falls squarely into the latter category.

“Kaseh Aries began through a common interest and passion among us friends for Malay romance novels,” Hamisah Abdul Rahman, one of the founders, says.

“We all love books, in Malay and English. We had been reading Malay romance novels long before starting our own publishing house,” she says.

Founded in 2016 by a group of professional women, the company achieved profitability within a couple of years and has since increased revenue by 300 percent.

To date, Kaseh Aries has published 57 books, and some bestsellers have gone on to be adapted into TV dramas. This includes their biggest hit, “The Misadventures of Cik Reen & Encik Ngok Ngek” which has sold in the tens of thousands, topped the bestseller lists for Popular and MPH bookstores, and became a hit TV series for Astro last year.

“The Malay romance novel industry has a very strong community presence on social media, where most writers and publishers will post teasers of their upcoming novels,” Hamisah explains when asked about their marketing.

“This is how we get to know about new novels and stories, even before we became publishers ourselves, and this is a practice we have emulated with our publishing house,” she says, referring to Kaseh Aries’ own use of social media to promote and directly sell to their customers via online portals.

Kaseh Aries books are also easily available in leading local bookstores like Popular and MPH. The founders also work together with Reader’s Heaven & Coffee, an independent local bookstore-cum-café two floors down from their offices in Bangi, which allows for a permanent physical space where their publications are stocked.

More than mainstream

Other independent publishers have decided to experiment with more thought-provoking content.

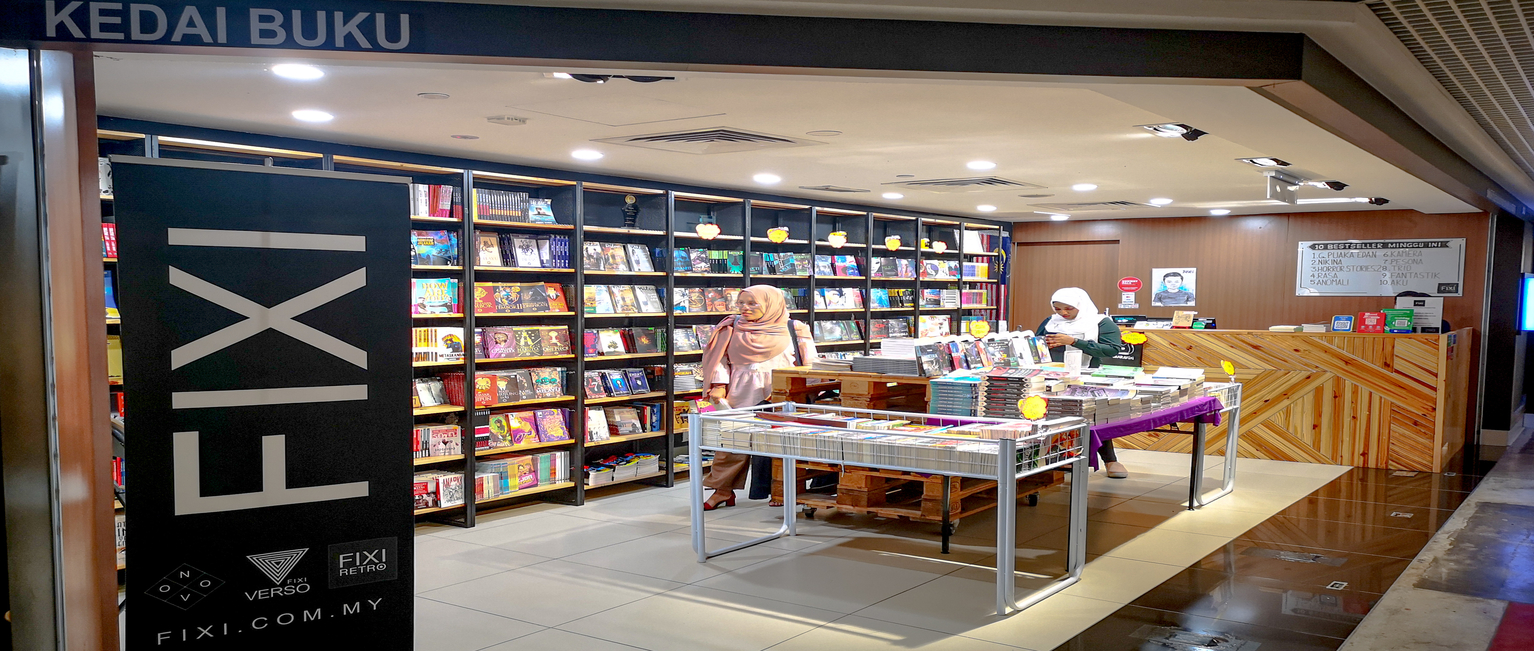

Buku Fixi, founded by filmmaker and writer, Amir Muhammad, has been a major industry player since its launch in 2011. The publishing house is known for putting out some of the more unusual local fiction available in the market.

“I started publishing simply because there were books I wanted to see which were not there,” Amir says.

“With Buku Fixi, we publish books for people who think serial killers are normal occurrences in Malaysia,” he jokes, referring to the often darker themes found in Fixi publications.

When it comes to reader demographics, Amir has had a similar experience to other publishers.

“What has worked would be those that strike a chord with young, mainly Malay, mainly female, readers,” he says.

But it goes beyond clean-cut romance. “What works for them is not that predictable,” Amir says, citing his two bestsellers “Asrama” and “Gantung” which fall in the horror genre, with romantic elements.

Nadia Khan, author of “Gantung”, gushed about the creative possibilities brought about by the independent publishing scene.

“The local indie publishing sector has definitely provided a greater variety of books and reignited the passion for reading, especially among the youths,” Nadia, who is also a screenwriter, says, as she describes the continuous positive feedback she has received, including the time thousands of fans showed up to a little publicised meet-and-greet for the web series adaptation of “Gantung”.

The president of the Malaysian Book Publishers Association (MABOPA), Ishak Hamzah echoed these sentiments.

“While most would say the independent publishers’ circle is wild, when you look at it in a positive way, they paved the way for something new, for creativity, and that is the point of this industry,” he said to The Malaysian Reserve earlier in the year.

Challenges to the industry

Amir’s efforts to publish novels in English, under the Fixi Novo imprint, have proved less successful.

“Malay-language books have access to a larger market, but also there is the “cultural cringe” factor when it comes to English books,” Amir says, referring to the phenomenon anthropologists describe as an internalised inferiority complex that leads people to dismiss their own culture in favour of others. In simple terms, this means English-language readers in Malaysia would rather read books by foreign writers rather than those penned by Malaysian authors.

Another issue has been the slow take-up of digital versions, such as electronic books (e-books). Most Malaysian readers still prefer to have a physical copy in their hands, a trend that is reflected worldwide, with consumers returning to the traditional book in droves, resulting in a peak in sales on sites like Amazon.

Although Hamisah reported that Kaseh Aries’ sales of e-books is encouraging, the bulk of their customers still prefer a physical book. Other publishers are more circumspect, pointing out that the preference for physical books limits the prospects and creativity of publishers.

“The bulk of our expenses is spent on printing and producing physical copies,” Amir Hafizi, founder of Maple Comics, says.

“So if we had a stronger take-up of e-books, that would free up resources for us to expand our titles, provide more choice and cater to a wider diversity of genres, tastes and styles as well as do more effective marketing,” he explains.

This situation becomes critical for smaller creative publishers, who are particularly vulnerable now that the publishing industry is suffering a downturn.

Earlier this year, MABOPA president Ishak Hamzah revealed to The Malaysian Reserve that the value of the local book industry has slipped below RM1 billion amid increasing closures among publishers, publications and book stores nationwide.

“Currently, the book industry is struggling with the issues between buyers having lesser spending power, while printing and publication are growing more expensive by the day,” he said, referring to the sluggish economy and rising costs.