Today, renewable energy systems are rapidly catching up, becoming more consistent, efficient and cheaper as innovations in technology continue to pour in.

Windfarms and solar power have been leading the charge for a while now. The two technologies are forecast to take the lion’s share of near future growth, with electricity generation from solar tripling and wind doubling.

“We are witnessing the transformation of energy system markets led by renewables and this is happening very quickly,” Dr Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA) told the Guardian.

“The cost of wind dropped by about one third in the last five to six years, and that of solar dropped by 80%,” said Birol.

These dramatic drops in cost are expected to continue, with onshore wind likely to come down by at least 15 per cent and big solar by 25 per cent by 2021.

“The decline in [cost of] renewables was very sharp and in a very short period of time. This is unprecedented,” Birol explained.

Alarming Urgency

As threats of intensifying climate change hastened by the consumption of fossil fuels, scientists, private industry and nation states have grown increasingly committed in their search for viable alternative sources of energy.

Investments in renewable energy technologies worldwide reached more than US$286 billion in 2015, led by China and the United States, while more than half of all new electricity capacity installed is now renewable.

To date, clean energy sources have mainly come from solar, wind, geothermal, biofuels, biomass and hydro, but historically, they have struggled to compete with carbon-based fuels when it comes to cost and reliability of energy supply.

Reza Abedi, a former executive at Sime Darby Renewables, has researched the technological innovations that have made these reductions in price possible.

“Many clean energy technologies like solar have reached parity, which means they can beat conventional electricity sources on price while matching their performance in many countries,” he says.

“For instance, wind turbine technology has made large strides with ever larger and taller turbines being made thanks to advances in materials which translates to more energy output per turbine.”

The growth in large offshore wind farms, coming online in recent years, especially in Europe, is another exciting development.

“Out at sea there's nothing obstructing the wind so wind speeds tend to be steadier and higher than on land,” Reza elaborates. “This allows wind turbine farms to generate more electricity consistently.”

A global revolution

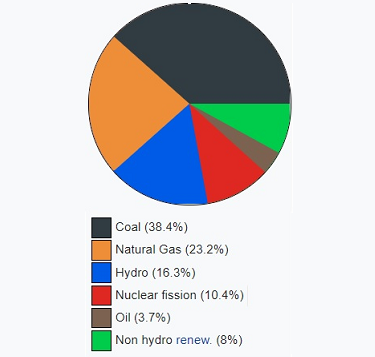

Globally, renewables’ share of total energy generation and consumption is growing.

At least 30 nations report more than 20 per cent of energy supply coming from renewables, while Iceland and Norway are already meeting all their energy needs from clean sources.

World power generation, 2016 [SOURCE: International Energy Agency]

Encouragingly, the rise in clean energy has not been limited to first world nations.

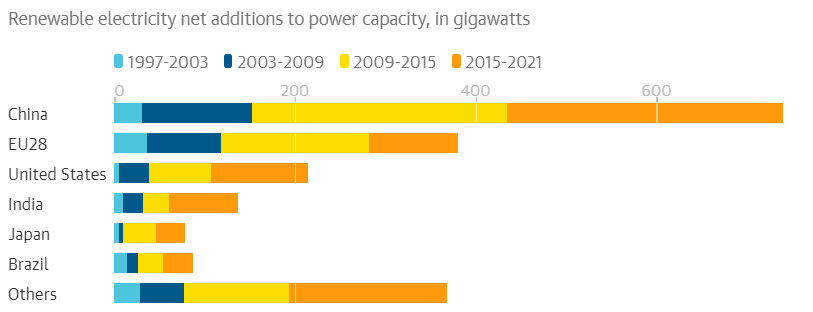

“This growth of renewables is led by the emerging countries in the years to come, rather than the industrialised countries,” IEA chief Birol said.

China will lead the world for growth in renewable energy, the agency reported.

“China alone is responsible for about 40 per cent of growth in the next five years. When people talk about China, they think about coal, but it is changing,” Birol said.

In 2016, a record high of 153GW net renewable electricity capacity was installed globally, an increase of 15 per cent on the year before.

[SOURCE: International Energy Agency, 2018]

China is well on their way to adding a further 305GW in the five years over 2016 to 2020, followed by India with 76GW.

“The reduction in cost of solar panels has led to many mega solar projects taking off,” Reza says.

“Last year, China opened the world's largest floating solar farm on a lake that formed over a collapsed coal mine.”

Reza was also impressed by the creative schemes coming from other emerging economies that have taken advantage of the latest designs and technologies.

“Most of the advancement in solar is in innovative business models in Africa and India, such as pay-to-own schemes for solar energy that brings renewable energy to rural communities.

“This is in part realized by the modular form of solar panels which makes installation easy as it doesn't need a large space,” he clarifies.

Still a long road ahead

Despite all the recent advancements, there is still a long way to go before renewable energy becomes a fact of life for most people.

Although renewables account for more than 50 per cent of net capacity additions and the IEA expects it to reach 60 per cent by 2021, it remains a relatively small share of the world’s electricity.

“When we think in terms of the total primary energy sources humanity consumes, it seems like renewables aren't making much progress at only 3.6 per cent of global primary energy,” Reza says.

Even the most positive figures predict that clean energy will account for no more than 28 per cent of electricity generation by 2021, with much still coming from environmentally damaging hydropower dams.

Despite the rapid growth expected in coming years, the IEA has said it will not be sufficient to meet the targets of the international Paris agreement of keeping temperatures below 2C, the threshold for dangerous warming.

“It’s a paradigm shift and the initial cost is high,” Dr Jessie Siaw, senior lecturer at SEGi University points out.

Dr Siaw thinks that more real-life examples would help to integrate renewable energy into regular life, including positive exposure in public places.

“People need to see to believe,” she opines.

“If public places are installed with renewable energy systems, and we promote them in a way that it becomes an attraction, then perhaps the acceptance would be faster.

Reza agrees that awareness is a big part of the solution.

“Clean energy will only increase in share due to economics, and growing awareness of climate change and the need to mitigate its impacts by reducing emissions,” he says.

IEA chief Birol contends that the biggest barrier to complete acceptance of renewables is actually the inconsistency of governments’ commitment.

“The issue is not the predictability of solar and wind, it is the predictability of government policies because investors need to see what their prospects are. This is the main challenge I see in the renewable energy sector.”